In mid-February I received a cancer diagnosis and by the end of the first week of March the offending body parts had been removed, three weeks in total give or take. I was in an express lane. It was good to know there was one. So often it feels like there’s no lane whatsoever in health care, every person for themself. Recovery, on the other hand, is taking its time. It’s a slow, unpaved back lane in a remote part of the world unconnected to normal daily existence. I have it to myself.

Ever since the surgery my body has taken to sending out distress calls. Left side, back: Hello, says the now vacated space, Has anyone seen my kidney? It communicates in SOS-like jabs like I’m a container ship and someone’s stuck in my hull. The doctor assures me that phantom organ pain is very rare and not what I’m experiencing. So maybe it's the adrenal glands. Who took our seat, they ask. They seem to be trying to burrow into my ribs, hanging on for dear life. Or distress calls that issue from the incisions themselves or their side effects, the neuropathy. It seems the nerves that typically lend feeling to my upper left leg were severed during surgery. The calls are all plaintive and pathetic, sad and melancholy. So far no one’s saying “Thank god we’re rid of that fucking kidney, such a baby.” Where’s the gratitude?

By my estimation, reading the treasure map that is the surface of my stomach, a half dozen laparoscopic entry points and a single eight-inch incision from navel to pubis, the surgeon had to travel twelve inches, at times wrist deep, I imagine, in tight, squishy quarters, pulling things out as she went, the rest of the my organs elbowed aside. That’s how it feels.

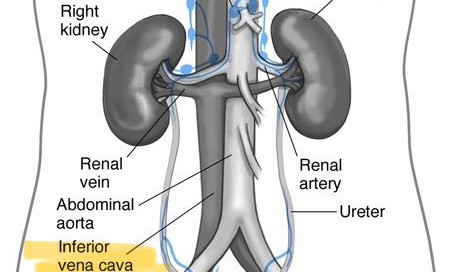

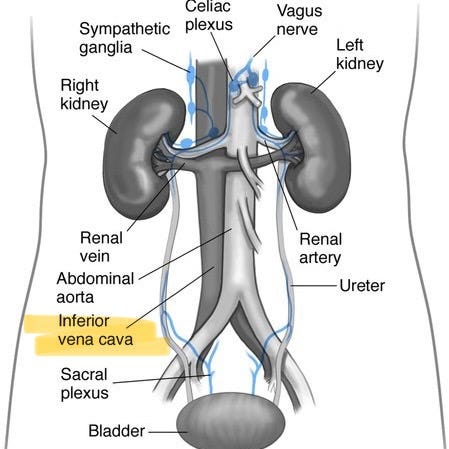

At a follow-up visit I dig for clues as to why it hurts so much. She reminds me that the surgery was challenging. Yes, I say, Tell me more. I’m onto something. She reminds me of her surprise at discovering I had two of one organ, vena cavas plural. As organ names go it doesn’t roll off the tongue. Is it important? Turns out it’s the vein, a tube, really, that runs the length of the torso, northbound, carrying blood back to the heart to be reoxygenated after its trip to the extremities. It takes a bathroom break at the kidneys. The surgeon had never seen two inferior vena cavas before and needed a phone consult before she could continue, the answer bearing on next steps. I’m now convinced that we’re all human Kinder Eggs, surprises lurking just beneath our surface, blissfully unaware of the existence of intruders or abnormalities and getting on just fine. Eventually she closes me back up. Now, however, everything in there is annoyed. Irritated. My parts are not happy with their new rearranged whole. They weren’t meant to be ruffled or to see the light of day and now that they’ve seen it they can’t unsee it. They’re traumatized. Resentful. But I did it for you, I say.

The main character in a book I’ve been reading has so far received daily beatings and a stabbing at the hands of fellow prisoners and been relieved of two of his teeth. He’s in a Mexican jail circa 1940. Moments ago, now free, he was shot in the leg and has himself cauterized the entry and exit wounds, front and back, with a pistol barrel made red hot in a campfire. I lie in my kidney-reduced state feeling chastened by his physical and emotional fortitude, if not his it would be by that of one of innumerable other real life unfortunates that I read and hear about in the news each day, the victims of myriad forms of violence. I have nothing to complain about. My wounds were sustained in a controlled setting in sterile conditions under general anesthetic overseen by a surgeon who mostly knew what she was doing and then I was ministered to by a steady stream of nurses. I cringe to think of how I’d do in my friend the fictional character’s shoes. Not well I think. He does, however, speak for both of us when he says “He hadn’t known how stupid pain could make you and he thought it should be the other way around or what was the good of it.”*

We take the simple things for granted. An untethered crotch, for instance. Delightful. It took only a fraction, mere nanoseconds, of the three weeks I spent with mine on a leash to develop a profound appreciation for its previously unfettered and free state. “Do not have sex while you have a catheter” read the care instructions and I tried to picture exactly what that would look like if I attempted it and was saddened to now know definitively that I’d never experienced the kind of passion that made such instruction even remotely necessary. I am, of course, grateful to Frederick Foley, the inventor of the catheter, whose dedication to humanity’s unobstructed peeing gave my own sutured bladder, fresh from the ectomy wars of Kidney and Ureter, time to heal.

I am grateful for all of it, frankly. This time-out is a pause. When discomfort alternating with pain doesn’t tire the hell out of me it allows me to think. At sixty-four, a brain surgery already under my belt, I know recovery is not swift and that physical challenges are only in their ascendancy. Never have I done so little, rested so much, and felt so supremely unbothered about it. Boredom? I look forward to it. When it again shows its face I’ll know I’m better. By then I may even have a clearer idea of how I want to honour and use my remaining good health.

*Cormac McCarthy, All the Pretty Horses

Figure: Allen PD. Anesthesiafor Renal and Urinary Tract Diseases. In: Vacanti C, Segal S, Sikka P, Urman R, eds. Essential Clinical Anesthesia. Cambridge University Press; 2011:617-630.

You are the epitome of equanimity. Funny and serious. Annoyed at pain and accepting of it. I'm glad you're on the mend. Let me know when you can drink wine or beer again. Or even if you're only up for water. You seem to be excelling at "taking care".

Brilliant